- Home

- About Us

- Chapters

- Study Design and Organizational Structure

- Study Management

- Tenders, Bids, and Contracts

- Sample Design

- Questionnaire Design

- Instrument Technical Design

- Translation

- Adaptation

- Pretesting

- Interviewer Recruitment, Selection, and Training

- Data Collection

- Paradata and Other Auxiliary Data

- Data Harmonization

- Data Processing and Statistical Adjustment

- Data Dissemination

- Statistical Analysis

- Survey Quality

- Ethical Considerations

- Resources

- How to Cite

- Help

Overview

Peter Mohler, Brita Dorer, Julie de Jong, and Mengyao Hu, 2016

(2010 Version: Janet Harkness, Brita Dorer, and Peter Ph. Mohler)

Translation is the process of expressing the sense of words or phrases from one language into another. It is also known as one type of asking the same questions and translating (ASQT) as discussed in Questionnaire Design (where we also discuss asking different questions (ADQ) and its correspondence to Adaptation). Another type of ASQT is decentering (also discussed in Questionnaire Design). Given that the former approach is more commonly used in cross-cultural research, in this chapter, we mainly focus on translation from one language to another.

Following terminology used in the translation sciences, this chapter distinguishes between 'source languages' used in 'source questionnaires' and 'target languages' used in 'target questionnaires.' The language translated out of is the source language; the language translated into is the target language.

Translation procedures play a central and important role in multinational, multicultural, or multiregional surveys, which we refer to as '3MC' surveys. Although good translation products do not assure the success of a survey, badly translated questionnaires can ensure that an otherwise sound project fails because the poor quality of translation prevents researchers from collecting comparable data.

The guidelines in Translation: Overview provide an overview of the translation process. In addition, there are six other sets of guidelines focusing on specific aspects of the translation process: Translation: Management and Budgeting, Translation: Team, Translation: Scheduling, Translation: Shared Language Harmonization, Translation: Assessment, and Translation: Tools.

Total Survey Error (TSE) is widely accepted as the standard quality framework in survey methodology [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UAYFD7FE},{2265844:8BP5AT5I},{2265844:BWMUUHCE}"]: “The total survey error (TSE) paradigm provides a theoretical framework for optimizing surveys by maximizing data quality within budgetary constraints. In this article, the TSE paradigm is viewed as part of a much larger design strategy that seeks to optimize surveys by maximizing total survey quality; i.e., quality more broadly defined to include user-specified dimensions of quality” [zotpressInText item="{2265844:8BP5AT5I}"]. See Survey Quality for more information. Seen from a TSE perspective, successful translation is a cornerstone of survey quality in 3MC surveys and comparative research.

A successful survey translation is expected to do all of the following: keep the content of the questions semantically similar; keep the question format similar within the bounds of the target language; retain measurement properties, including the range of response options offered; and maintain the same stimulus [zotpressInText item="{2265844:KIP6EVCR}"]. Based on growing evidence, the guidelines presented below recommend a team translation approach for survey instrument production [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:4S267T9N},{2265844:WIZ9W4KX},{2265844:3DJR6SHM},{2265844:TNMYF2MY}"]. Other approaches, such as back translation, although recommended in the past, do not comply with the latest translation research.

As discussed in Questionnaire Design, there are three major approaches to questionnaire development for 3MC surveys: asking the same questions and translating (ASQT), adapting to new needs and asking different questions (ADQ), or using a mixed approach that combines ASQT and ADQ. That is to say, to design cross-culturally comparable surveys, the translation team needs to closely collaborate with other teams, such as an adaptation team; see Questionnaire Design and Adaptation for more information. The guidelines address, at a general level, the steps and protocols recommended for survey translation efforts conducted using a team approach. The guidelines and selected examples that follow are based on two principles:

▪ Evidence: recommendations are based on evidence from up to date literature.

▪ Transparency: examples given should be accessible in the public domain.

Many examples draw on the European Social Survey (ESS), which is the current leader in research on, and the implementation of, modern translation procedures and transparent documentation, including national datasets. Thus, it serves as a model for these guidelines.

In a team approach to survey translation, a group of people work together. Independently from each other, individual translators produce initial translations; reviewers then review translations with the translators, and one (or more) adjudicator decides whether the translation is ready to move to detailed pretesting (See Pretesting) and when the translation can be considered to be finalized and ready for fielding.

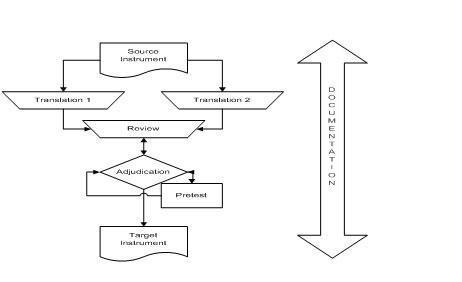

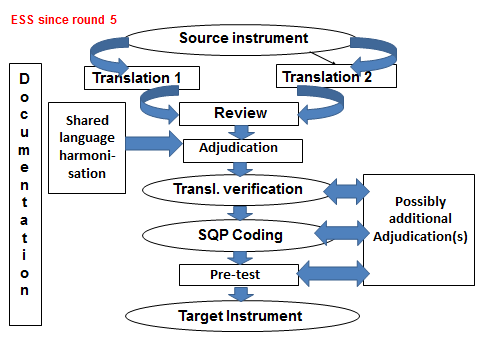

Figure 1 below presents the TRAPD (Translation, Review, Adjudication, Pretesting, and Documentation) team translation model. In TRAPD, translators provide the draft materials for the first discussion and review with an expanded team. Pretesting is an integral part of the TRAPD translation development. Documentation of each step is used as a quality assurance and monitoring tool [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:2MJMKXPF},{2265844:RK729MUW},{2265844:6X7KLZ7U}"].

Figure 1: The TRAPD Team Translation Model.

Procedures are partially iterative in team translation. The review stage reviews and refines initial parallel translations. Adjudication, often a separate step from review, can lead to further modifications of the translation before it is signed off for pretesting (see Pretesting). Pretesting may again result in modifications before the adjudicator signs off on the version for final fielding.

Team approaches to survey translation and translation assessment have been found to be particularly useful in dealing with the fairly unique challenges of survey translation. The team can be thought of as a group with different talents and functions, bringing together the mix of skills and discipline expertise needed to produce an optimal version in the survey context where translation skill alone is not sufficient. Team translation counteracts the subjective nature of translation and assessment procedures that do not deliberate translation outcomes in a professional team. In doing so, team translation can achieve systematic intersubjective agreement as required in standard methodology. In addition, while providing a combined approach which is qualitatively superior, it is not a more expensive or more complicated procedure.

There are a number of other advantages to the team approach as well. The ability for each member of the translation team to document steps facilitates adjudication, as well as provides information for secondary analysis which can inform versions for later fieldings. Additionally, the team approach allows for a considered but parsimonious production of translations which share a language with another country. Some or all of these procedures may need to be repeated at different stages (see Figure 2). For example, pre-testing and debriefing sessions with fielding staff and respondents will lead to revisions; these then call for further testing of the revised translations.

Team approaches to survey translation and assessment have been found to provide the richest output in terms of (a) options to choose from for translation and (b) a balanced critique of versions [zotpressInText item="{2265844:K4E3JQ52},{2265844:KXABGS6W},{2265844:A6C8D6DW},{2265844:LAH6XJPS},{2265844:PSDFM568}"]. The team should bring together the mix of skills and disciplinary expertise needed to decide on optimal versions. Collectively, members of this team must supply knowledge of the study, of questionnaire design, and of fielding processes [zotpressInText item="{2265844:9ICRC77B},{2265844:YFYE79Z4}"]. The team is also required to have the cultural and linguistic knowledge needed to translate appropriately in the required varieties of the target language (see [zotpressInText item="{2265844:K4E3JQ52}" format="%a% (%d%)" etal="yes"] and [zotpressInText item="{2265844:PSDFM568}" format="%a% (%d%)" etal="yes"]). Further consideration of advantages that team efforts have over other approaches can be found in [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:4S267T9N},{2265844:WVHEPQY3}" format="%a% (%d%)"], [zotpressInText item="{2265844:WIZ9W4KX}" format="%a% (%d%)"], and [zotpressInText item="{2265844:LAH6XJPS}" format="%a% (%d%)"].

Each stage of the team translation process builds on the foregoing steps and uses the documentation required for the previous step to inform the next. In addition, each phase of translation engages the appropriate personnel for that particular activity and provides them with relevant tools for the work at hand. These tools (e.g., documentation templates; see Appendix A) increase process efficiency and make it easier to monitor output. For example, translators producing the first, independent translations (‘T’ in the TRAPD model) are required to keep notes about any queries they have on their translations or the source text. These notes are considered along with the translation output during the next review stage, in which reviewers work together with the translators [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:2MJMKXPF},{2265844:RK729MUW}" format="(%a%, %d%, %p%)" etal="Yes" separator="comma"].

Team translation efforts work with more than one translator. Translators produce translation material and attend review meetings. Either each translator produces a first, independent translation of the source questionnaire (double or full/parallel translation), or each translator gets parts of the source questionnaire to translate (split translation) [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:LAH6XJPS},{2265844:VM63FDRU}"]. The double translations or the sections of the split translation are refined in the review stage and possibly again after subsequent steps, as just described.

Whenever possible, translation efforts that follow a team approach work with more than one initial version of the translated text. A sharing of these initial versions and discussion of their merits is a central part of the review process. Two initial translations, for example, can dispel the idea that there is only one 'good' or 'right' translation. They also ensure that more than one translation is offered for consideration, thus enriching the review discussion. This encourages a balanced critique of versions [zotpressInText item="{2265844:K4E3JQ52},{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:WIZ9W4KX},{2265844:PSDFM568}"]. Contributions from more than one translator also make it easier to deal with regional variance, idiosyncratic interpretations, and translator oversight [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:RK729MUW},{2265844:KIP6EVCR}" etal="yes"].

Survey translations also often call for sensitivity for words people speak rather than words people write. Apart from ensuring the needed range of survey expertise and language expertise, the discussion that is part of team approaches (the Review session, that is, ‘R’ in the TRAPD scheme) is more likely to reveal vocabulary or vocabulary level/style (register) problems which might be overlooked in a review made without vocalization. Pretesting may, of course, reveal further respondent needs that 'experts' missed.

As noted, team-based approaches aim to include the translators in the review process. In this way, the additional cost of producing two initial/parallel translations would be offset by the considerable contributions the translators can bring to review assessments. Since they are already familiar with the translation challenges in the texts, they make the review more efficient. Split translation arrangements can still capitalize on the advantages of having more than one translator in the review discussion, but avoid the cost of full or double translations. The advantages and disadvantages of each approach are discussed under Guidelines 3 and 4 below (see also [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD}" format="%a% (%d%)"] and [zotpressInText item="{2265844:VM63FDRU}" format="%a% (%d%)"]).

Goal: To create and follow optimal procedures to standardize, assess, and document the processes and outcomes of survey questionnaire translation.

1. Plan translation as an integral part of the study design. This planning should include all the elements that will be part of the translation procedures (e.g., selection of team members, language harmonization/shared language arrangements), and should accommodate them in terms not only of procedural steps but with regard to hiring, training, budgeting, time schedules, and the questionnaire and translation production processes.Rationale

Survey translation efforts are part of the target language instrument development and should be treated accordingly. In addition, when translations are produced in order to take part in a larger comparative project, forethought and a clear direction to planning and implementing translation will help produce translations across multiple locations which comply with project requirements.

Restrictions

Some surveys, such as Eurobarometer, are designed using English and French simultaneously as source languages. That procedure involves complex issues of linguistic equivalence beyond the realm of translation [zotpressInText item="{2265844:6X7KLZ7U}"].

These guidelines only refer to studies using one single source language. Studies using more than one source language would need to implement additional steps that are not discussed in these guidelines.

Procedural steps

1.1 Define the following:

1.1.1 The larger vision (e.g., a successfully implemented survey).

1.1.2 The concrete goal (e.g., a well-developed translation for the various contexts and populations).

1.1.3 Important quality goals (e.g., a population-appropriate translation, comparability with source questionnaire, efficiency and feasibility of translation procedures, timeliness).

1.1.4 Relevant factors (e.g., schedules, budget, personnel available, unexpected events).

1.1.5 Tasks involved (e.g., assembling personnel and the translation documents; preparing tools, such as templates; training personnel; producing and reviewing translations; pretesting; copyediting).

1.2 Identify core team members (those people required for the team translation effort). (See Appendix B for specific tasks of each core team member and other team players identified below.)

1.2.1 Translators.

1.2.2 Reviewer(s).

1.2.3 Adjudicator(s).

1.3 Identify any other team players who may be required, based upon the size of the project, the mode of data collection, etc.

1.3.1 Copyeditor(s).

1.3.2 Co-coordinator.

1.3.3 Substantive experts.

1.3.4 Programmers.

1.3.5 Other experts, such as visual design experts, adaptation experts.

1.3.6 External assessors.

1.3.7 Back-up personnel.

1.4 Determine whether regional variance in a language or shared languages need to be accommodated; decide on strategies for this as needed (see Translation: Shared Language Harmonization).

1.4.1 Select, brief, and train personnel (see Translation: Team). In training personnel, consult Appendix C for details on and examples of common causes of mistranslation. Identify the in-house and external staff and consultant needs for the project and follow appropriate selection, briefing, and training procedures for each person or group.

1.4.2 Identify, acquire, and prepare the materials for translation. In addition to the source questionnaire, these may include advertising material, interviewer manuals, programmer instructions, and any supporting materials such as 'show cards,' as well as statements of informed consent.

1.4.3 Clarify payment arrangements for all involved (see Translation: Management and Budgeting).

1.4.4 Create a time schedule and identify project phases and milestones for members of the team (see Translation: Management and Budgeting).

1.4.5 Arrange for back-up team members in the event of unavailability or illness.

1.4.6 Decide on the mode and schedule of meetings (face-to-face, webcasting, or conference calls) and materials to be used at meetings (e.g., shared templates, software tools, documents deposited in e-room facilities, dictionaries, paper-and-pencil note-taking).

1.4.7 Decide on other communication channels and lines of communication (e.g., for reporting delays, illness, completion, and deadlines).

1.4.8 Decide whether each translator will prepare a full translation (double/parallel translation) or whether the material to be translated will be divided among the translators (split translation).

1.4.9 Decide on deliverables for translation from all study countries (e.g., information on national translation teams, documentation of national versions and translation discussions, etc.).

1.4.10 Translation involves understanding of meaning of the source text and conveying this meaning in the target language with the means of the target language. To this end, identify elements of the source questionnaire that would benefit from the use of translation annotations and explicitly invite countries to point out in advance where they would like annotations. As mentioned in Questionnaire Design, using advance translations or translatability assessment at the beginning of the translation process can effectively minimize later translation problems (see also Appendix D for more on annotations and [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CJWMN3W9}" format="%a% (%d%)"] for more on carrying out advance translations).

Lessons learned

1.1 Mistaken translation can greatly jeopardize research findings. As reported in the article “World values lost in translation” in the Washington Post [zotpressInText item="{2265844:TWSH5BYZ}"], many translated terms showed different associations than the term used in English. It also shows the changes of translation in later waves of the survey made trend analysis impossible for some countries in the World Value Survey. It thus prevents the analysis on the stability of change in values, which is one of the main goal of the survey.

1.2 It is question development, rather than question translation, that is the real key to comparative measurement. Questions properly developed for the comparative context give us the chance to measure what we intend to measure and to ask respondents what we intend to ask. At the same time, poorly translated questions (or response categories, instructions, show cards, or explanations) can rob us of that chance—they can mean that respondents are not, in fact, asked what they should be asked. Seen against the costs and effort involved in developing and implementing a comparative study, translation costs are low. On the other hand, the cost of inappropriate versions or mistakes in questionnaire translations can be very high [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}"].

1.3 In major efforts, the bigger picture must first be considered to confirm which routine or special tasks are vital and which are not. It is easy to focus on procedures which are familiar, and thus inadvertently miss other vital elements. For example, if consistency in terminology across versions is not something a project leader has usually considered, procedures to check for this might be overlooked in planning.

1.4 The number of translations required varies among multilingual survey projects. The Afrobarometer Survey, the Asian Barometer Survey, and the ESS Source specify that every language group that is likely to constitute at least 5% of the sample should have a translated questionnaire.

1.5 Planning quality assurance and quality control should go hand-in-hand. When planning the project or procedure, it is also time to plan the quality assurance and quality control steps. For example, in planning the translation of response scales, steps to check that scales are not reversed or a response category is not omitted can be incorporated into a translation template.

1.6 It is essential to pay close attention to the type of response scales used and the translation of response scale options. For example, in an analysis of data from five surveys conducted in four different countries (China, Germany, Sweden, and the United States) asking respondents to rate their health using a balanced scale and an unbalanced scale, [zotpressInText item="{2265844:5SH7RPZ6}" format="%a% (%d%)"] found that inconsistent translation of the scale point “fair” on the unbalanced self-rated health scales produced different response distributions, rendering the resultant data less comparable.

2. Have two or more translators produce initial, parallel translations. If possible, have each translator produce a full (parallel) translation; if that is not possible, aim to create overlap in the split translation sections each translator produces.Rationale

Having more than one translator work on the initial translation(s) and be part of the review team encourages more discussion of alternatives in the review procedure. It also helps reduce idiosyncratic preferences or unintended regional preferences. In addition, including the translators who produced the first translations in the review process not only improves the review but may speed it up as well.

Procedural steps

2.1 Determine lines of reporting and document delivery and receipts.

2.1.1 Translation coordinators typically deliver materials to translators. Coordinators should keep records of the delivery of materials and require receipt of delivery. This can be done in formal or less formal ways, as judged suitable for the project complexity and the nature of working relationships.

2.1.2 The project size and complexity and the organizational structure (whether centralized, for example) will determine whether translation coordinators or someone else actually delivers materials and how they are delivered.

2.2 Determine the protocol and format for translators to use for note-taking, asking translation queries, and providing comments on source questions, on adaptations needed, and translation decisions. (See Appendix A for documentation templates.)

2.3 Establish deadlines for deliveries, including partial translations (see below) and all materials for the review session.

2.3.1 If working with new translators, consider asking each translator to deliver the first 10% of their work by a deadline to the coordinator (senior reviewer or other supervisor) for checking. Reviewing performance quickly enables the supervisor to modify instructions to translators in a timely fashion and enables hiring decisions to be revised if necessary.

2.3.2 Following the established protocol for production procedures and documentation, each translator produces their translation and delivers it to the relevant supervisor.

2.4 Where several different translated questionnaires are to be produced by one country, translation begins from the source questionnaire, not from a translated questionnaire (e.g., for a questionnaire with a source language of English and planned translations into both Catalan and Spanish, both the Catalan and Spanish translations should originate from the English version, rather than the Catalan originating from the Spanish translation).

2.5 Any translated components (e.g., instructions, response scales, replicated questions) used in earlier rounds of a survey that are to be repeated in an upcoming round should be clearly marked in what is given to the translators. See also Appendix E regarding material in existing questionnaires. After receiving the translated materials, have the coordinator/senior reviewer prepare for the review session by identifying major issues or discrepancies in advance. Develop procedures for recording and checking consistency across the questionnaire at the finish of each stage of review or adjudication. (See Appendix A for documentation examples.)

Lessons learned

2.1 The more complex the project (e.g., number of translations), the more careful planning, scheduling, and documentation should be (see Translation: Management and Budgeting).

2.2 Since the aim of review is to improve the translation wherever necessary, discussion and evaluation are at the heart of the review process. The senior reviewer or coordinator of the review meetings must, if necessary, help members focus on the goal of improvement. In line with this, people who do not respond well to criticism of their work are not likely to make good team players for a review.

2.3 Review of the first 10% of the initial translation (in case you are working with a new translator) may indicate that a given translator is not suitable for the project, because it is unlikely that serious deficiencies in translation quality can be remedied by more training or improved instructions. If this is the case, it is probably better to start over with a new translator. See also Translation: Team for further detail on skill and product assessment.

2.4 The first or initial translation is only the first step in a team approach. Experience shows that many translations proposed in first drafts will be changed during review.

2.5 If translators are new to team translation or the whole team is new, full rather than a split procedure is recommended whenever possible to better foster discussion at the review and avoid fixation on 'existing' text rather than 'possible' text.

2.6 Not every single word needs to be translated literally, as in a word-for-word version. Consider the survey item: “Employees often pretend they are sick in order to stay at home.” In this example from ESS Round 4, a country needed to use two words in order to translate “employees” (employees and workers), since a one-word literal translation for 'employees' in their language would convey only employees engaged with administrative tasks. The British English word ‘employees’ covers all those who work for any employer regardless of the type of work they do. Brief documentation may be useful to make it clear to data users and researchers why this addition was needed. This could, for instance, be documented by including a comment in a documentation form; see also examples in Appendix A. However, whenever decisions such as this are made, careful consideration should equally be given to the issue of respondent burden, question length, and double-barreled items.

2.7 It is important to inform team members that changes to the initial translations are the rule, rather than the exception. The aim of a review is to review AND improve translations. Changes to initial translations should be expected and welcomed.

2.8 Providing templates to facilitate note-taking will encourage team members to do just this. Notes collected in a common template can be displayed more readily for all to see at meetings. The use of a documentation template allows translators to make this documentation while doing the translation (see examples in Appendix A). A few key words suffice; comments do not have to be as fully phrased as in an essay. Review and adjudication can then draw on these comments; review and adjudication become more efficient since reviewers and adjudicators do not have to 'reinvent the wheel.' It may seem cheaper only to work with one translator and to eschew review sessions, since at face value, only one translator is being paid for their translation and there are no review teams or team meetings to organize and budget for. In actuality, unless a project takes the considerable risk of just accepting the translation as delivered, one or more people will be engaged in some form of review. When only one translator is involved, there is no opportunity to discuss and develop alternatives. Regional variance, idiosyncratic interpretations, and inevitable translator blind spots are better handled if several translators are involved and an exchange of versions and views is part of the review process. Group discussion (including input from survey fielding people) is likely to highlight such problems. A professional review team may involve more people and costs than an ad hoc informal review, but it is a central and deliberate part of quality assurance and monitoring in the team translation procedure. Team-based approaches include the translators in the review process. Thus, the cost of using two translators to translate is offset by their participation in assessment. And since they are familiar with translation problems in the texts, the review is more effective. The team approach is also in line with the so-called ‘four eyes principle,’ requiring that every translation is double-checked by a second equally qualified translator in order to minimize idiosyncrasies in the final translation.

2.9 In addition, even in a team translation procedure, translation costs will make up a very small part of a survey budget, and cannot reasonably be looked at as a place to cut costs, and experience gained in organizing translation projects and selecting strong translators and other experts is likely to streamline even these costs (see Translation: Management and Budgeting). The improvements that team translations offer justify the additional translator(s) and experts employed.

2.10 The burden of being the only person with language and translation expertise in a group of multiple other experts can be extreme. If more than one translator is involved in review, their contributions may be more confident and consistent and also be recognized as such.

2.11 When translators simply 'hand over' the finished assignment and are excluded from the review discussion, the project loses the chance to have translator input on the review and any discussion of alternatives. This seems an inappropriate place to exclude translator knowledge.

2.12 Relying on one person to provide a questionnaire translation is particularly problematic if the review is also undertaken by individuals rather than a team (these are reasons for working in teams rather than working with individuals).

2.13 Even if only one translator can be hired, one or more persons with strong bilingual skills could be involved in the review process. (The number might be determined by the range of regional varieties of a language requiring consideration for the translation. Bilinguals might not be able to produce a useable translation, but could probably provide input at the review after having gone through the translation ahead of the meeting.)

2.14 Translators should ask themselves ‘What does this survey item mean in the source questionnaire?’, and then put this understanding into words in their own, that is, the target language. They should produce translations that do not reduce or expand the information to the extent that the meaning or the concept of the original source question is no longer kept. It is important that translated items trigger the same stimulus as the source items (this corresponds to the ‘Ask-the-Same-Question’ approach). However, ensuring a fully equivalent translation may sometimes turn out to be impossible; in particular, if two languages do not have terms that match semantically, or even have equivalent concepts at all. In these cases, the best possible approximation should be striven for and the lack of ‘full’ equivalence clearly noted [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}"].

2.15 If a country’s team comes across interpretation problems that they are unable to solve, they should be encouraged to query the overall coordinator for the project, as the issue may reveal ambiguities that should be clarified for all countries in a multi-country project.

2.16 Translators should be mindful of clarity and fluency. In general, translators should do their best to produce questions that can readily be understood by the respondents and fluently read out by the interviewers, otherwise the measurement quality of the question may be compromised. Writing questions that can be understood by the target population requires not only taking into account usual target language characteristics, but also involves taking into account the target group in terms of their age, education, etc. People of various origins should be able to understand the questionnaire in the intended sense without exerting particular effort [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}"].

2.17 Translators should use words that the average population can understand. Be careful with technical terms. Only use them when you are confident that they can be understood by the average citizen. For example, in one of the ESS translations the ESS item “When you have a health problem, how often do you use herbal remedies?” the technical term “phytotherapie” ('phytotherapy') was used for “herbal remedies.” This translation was evaluated by an independent assessor as correct, but was probably not intelligible to most people [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}"].

2.18 Translators should try to be as concise and brief as possible in the translation, and not put additional burden upon the respondent by making the translation unnecessarily long. Also, if forced by language constraints to spell out things more clearly in the target language than in the source language (e.g. two nouns rather than one noun; a paraphrase rather than an adverb), always keep the respondent burden to the minimum possible [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}"].

3. If possible, have new teams work with two or more full translations.Rationale

Having new teams work with two or more full translations is the most thorough way to avoid the disadvantages of a single translation. It also provides a richer input for review sessions than the split translation procedure, reduces the likelihood of unintentional inconsistency, and constantly prompts new teams to consider alternatives to what is on paper.

Procedural steps

3.1 Have several translators make independent full translations of the same questionnaire, following the steps previously described in Guideline 2.

3.2 At the review meeting, have translators, a translation reviewer, and anyone else needed at that session go through the entire questionnaire, question by question. In organizing materials for the review, depending on how material is shared for discussion, it may be useful to merge documents and notes in the template (see Appendix A).

Lessons learned

3.1 The translation(s) required will determine whether more than two translators are required. Thus if, for instance, the goal is to produce a questionnaire that is suitable for Spanish-speaking people from many different countries, it is wise to have translators with an understanding of each major regional variety of Spanish required. If, as a result, 4 or 5 translators are involved, full translation can become very costly, and splitting the translation material is probably the more viable option.

3.2 Translators usually enjoy not having to carry sole responsibility for a version once they have experienced team work.

4. To save time and funds, have experienced teams produce split translations.Rationale

Split translations, wherein each translator translates only a part of the total material, can save time, effort, and expense. This is especially true if a questionnaire is long or multiple regional variants of the target language need to be accommodated [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:LAH6XJPS},{2265844:VM63FDRU}"].

Procedural steps

4.1 Divide the translation among translators in the alternating fashion used to deal cards in many card games.

4.1.1 This ensures that translators get a spread of the topics and possibly different levels of difficulty present in the instrument text.

4.1.2 This is especially useful for the review session—giving each translator material from each section avoids possible translator bias and maximizes translator input evenly across the material. For example, the Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) questionnaire has modules on financial topics, relationships, employment, health, and other topics. By splitting the questionnaire (more or less) page for page, each translator is exposed to trying to translate a variety of topics, and better able to contribute directly during review as a result.

4.1.3 Whenever possible, divide the questionnaire up in a way that allows for some overlap in the material each translator receives (see the first two 'Lessons learned' for this guideline).

4.1.4 Keep an exact record of which translator has received which parts of the source documents.

4.2 Have each translator translate and deliver the parts they have been given for the review meeting.

4.3 Use agreed-upon formats or tools for translation delivery for the review session. For example, if a template is agreed upon, then different versions and comments can be entered in the template to make comparison easier during review. (See examples in Appendix A).

4.4 Develop a procedure to check for consistency across various parts of the translation.

4.5 At the review meeting, have translators and the review team go through the entire questionnaire. When organizing materials for the review, depending on how material is shared for discussion, it may be useful to merge documents and notes (see Appendix A). Take steps to ensure that material or terms which recur across the questionnaire are translated consistently. For example, it is conceivable that two translators translate the same expression and come up with suitable but different translations. Source instrument references to a person's (paid) work might be rendered with "employment" by one translator, with "job" by another, and with "profession" by a third.

4.6 Similarly, it is conceivable that two translators translate the same expression and come up with suitable but different translations. Because they are not problematic, they might then not be discussed during review. Consistency checks can ensure that one translator’s translation of, say, “What is your occupation?” as something like “What work do you do?” can be harmonized with another translator’s rendering as something more like “What job do you have?” (for additional information on consistency, see [zotpressInText item="{2265844:GXPLUJSH}" format="%a% (%d%)"]).

4.1 It is often necessary to split the material to address issues of time, budget, or language variety. Even observing the card-dealing division of the material [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:LAH6XJPS}"], there is often no direct overlap in split translations between the material the different translators translate. Translators are thus less familiar with the challenges of the material that they did not translate than the sections they translated. This can reduce the detail of input at the question-by-question review meeting. The senior reviewer must therefore take care to stimulate discussion involving all translators of any section(s) where only one translation version is available.

4.2 Budget and schedules permitting, it is ideal to create some modest overlap in material translated. This allows the review team, including translators, to have an increased sense of whether there are large differences in translating approaches between translators or in their understanding of source text components at the draft production level.

4.3 Giving people time to prepare the materials for the review meeting and making sure that they are prepared is important for the meeting's success. Ad hoc suggestions and responses to translations are usually insufficient. Consistency checks can ensure that one translator's translation can be harmonized with another translator's possibly equally good but different rendering.

4.4 In checking for consistency, it is important to remember this procedure must not be only mechanical (for example, using a 'find' function in software). The source text may use one and the same term in different contexts with different meanings, while other language versions may need to choose different terms for different contexts. The opposite may also hold. Automatic harmonization based on 'words' is thus not a viable procedure. For example, the English word 'government' may need to be translated with different words in another language depending on what is meant. In reverse fashion, English may use different words for different notions which are covered by a single word or phrase in other languages. Examples: English 'ready' and 'prepared' can in some circumstances be one word in German; 'he' and 'she' are differentiated in English but not in Turkish or Chinese (see also [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}" format="%a% (%d%)"]).

4.5 Checks for general tone consistency are also needed: this means that it is important to use the same style in the entire survey instrument in terms of language register, politeness norms, or level of difficulty. There is, for instance, a difference in tone in English between talking about a person's 'job' and a person's 'profession,' or in referring to a young person as a 'child' and as a 'kid.'

4.6 Split translations may be helpful in the case of countries with shared languages, where there will be the benefit of input from the other countries’ translations. See Translation: Shared Language Harmonization for further discussion about split translations in countries with shared languages.

5. Review and refine draft translations in a team meeting. Review meetings may be in-person, virtual, or a mix of the two. The time involved depends upon the length and complexity of a questionnaire, the familiarity of the group with procedures, and disciplined discussion. The work may call for more than one meeting.Rationale

The team meeting brings together all those with the necessary expertise to discuss alternatives and collaborate in refining the draft translations—translation reviewers, survey experts, and any others that a specific project requires.

Procedural steps

5.1 Make all the initial translations available to team members in advance of the review meeting(s) to allow preparation.

5.2 Provide clear instructions to members on expected preparation for the meeting and their roles and presence at the meeting.

5.3 Arrange for a format for translations and documentation that allows easy comparison of versions.

5.4 Use the appropriate template to document final decisions and adaptations (see examples in Appendix A). See also Adaptation.

5.5 Appoint a senior reviewer with specified responsibilities.

5.6 Have the senior reviewer specifically prepare to lead the discussion of the initial parallel translations in advance. Prior to the meeting, this reviewer should make notes on points of difficulty across translations or in the source questionnaire and review translators' comments on their translations and the source documents with a view to managing.

5.7 Ask other team members to review all the initial translations and take notes in preparation for the meeting. The time spent on preparation will be of benefit at the meeting.

5.8 Have the senior reviewer lead the discussion.

5.8.1 The lead person establishes the rules of the review process.

5.8.2 They emphasize, for example, that most likely the team will change existing translations, and that the common aim is to collaborate towards finding the best solutions.

5.9 Have the senior reviewer appoint two revision meeting note-takers (any careful and clear note-taker with the appropriate language skills, and often the senior reviewer).

5.10 Have the team go through each question, response scale, instruction, and any other components comparing draft suggestions and considering other alternatives. Team members aim to identify weaknesses and strengths of proposed translations and any issues that arise such as comparability with the source text, adaptations needed, difficulties in the source text, etc.

5.11 Ensure that changes made in one section are also made, where necessary, in other places. Some part of this may be more easily made after the review meeting on the basis of notes taken.

5.12 Whenever possible, finalize a version for adjudication.

5.12.1 If a version for adjudication cannot be produced, the review meeting documentation should note problems preventing resolution.

5.13 At the end of the translation process (i.e., normally before, and, if needed, after the pretest), copyedit the translation in terms of its own accuracy (consistency, spelling, grammar, etc.).

5.14 Also, copyedit the reviewed version against the source questionnaire, checking for any omissions, incorrect filtering or instructions, reversed order items in a battery or response scale labels, etc.

Lessons learned

5.1 Guidelines are only as good as are their implementation. Quality monitoring plays an essential role. However, evaluation of survey quality begs many issues. Translators asked to assess other translators’ work may, for example, be hesitant to criticize or, if not, may apply standards which work in other fields but are not appropriate for survey translation. In the worst instance, they may follow criteria required by people who do not understand survey translation.

5.2 Much remains to be established with regard to survey translation quality. Group dynamics are important. The lead person/senior reviewer leads the discussion. When two suggested versions are equally good, it is helpful to take up one person's suggestion one time and another person's the next time. Given the objectives of the review, however, translation quality obviously takes priority in making decisions about which version to accept.

5.3 Time-keeping is important. The senior reviewer should confirm the duration of the meeting at the start and pace progress throughout. Otherwise, much time may be spent on early questions, leaving too little for later parts of the questionnaire.

5.4 It is better to end a meeting when team members are tired and re-convene later than to review later parts of the questionnaire with less concentration.

5.5 Practice taking documentation notes on points not yet resolved or on compromised solutions (see Translation: Team).

5.6 Not everyone needs to be present for all of a review meeting. Members should be called upon as needed. Queries for substantive experts, for example, might be collected across the instrument and discussed with the relevant expert(s) in one concentrated sitting.

6. Complete any necessary harmonization between countries with shared languages before pretesting.Rationale

In 3MC surveys, multiple countries or communities may field surveys in the same language. However, the regional standard variety of a language used in one country usually differs to varying degrees in vocabulary and structure from regional standard varieties of the same language used in other countries. As a result, translations produced in different locations may differ considerably. Harmonization should take place before pretesting to avoid unnecessary differences across their questionnaires.

Procedural steps

See Translation: Shared Language Harmonization.

7. Assess and verify translations, using some combination of procedures discussed in Translation: Assessment, potentially independent of formal pretesting.Rationale

Assessment of translations prior to pretesting can identify certain types of errors that are difficult to detect through pretesting alone, and also allow for a more accurate questionnaire for evaluation in the pretest.

Procedural steps

8. Have the adjudicator sign-off on the final version for pretesting.Rationale

Official approval may simply be part of the required procedure, but it also emphasizes the importance of this step and the significance of translation procedures in the project.

Procedural steps

8.1 If the adjudicator has all the skills needed (strong language ability in the source language and target language, knowledge of the study and of survey measurement and design issues), have them take part in the review session if possible. However, even in this case, it is advisable whenever possible to delay official signing-off to another day, thus leaving time for final checking of the decisions taken [zotpressInText item="{2265844:KIP6EVCR}"].

8.2 If the adjudicator does not have special relevant expertise, have them work with consultants to check that all procedures have been followed, that the appropriate people were involved, that documentation was kept, etc., according to procedural requirements. To assess the quality of review outputs, for example, the adjudicator can ask to have a list of all the perceived challenges and request to have concrete examples of these explained.

8.3 If the expertise of the adjudicator lies somewhere between these extremes, consider having them review the translation with the senior reviewer on the basis of the review meeting documentation.

8.4 Ensure again that changes made in one section are also made, if necessary, in other places.

Lessons learned

8.1 Emphasizing the value of finding mistakes at any stage in the production is useful. At the same time, a team effort usually shares responsibility. If things are missed, it is best in any instance if no one is made to feel solely responsible.

8.2 If a translation mistake means a question is excluded from analysis in a national study, the costs and consequences are high; in a comparative survey, the costs and consequences are even higher. Making team members aware of this may help focus attention. For instance, the German mistranslation in a 1985 International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) question regarding participation in demonstrations meant both the German and the Austrian data on this question could not be compared with other countries [zotpressInText item="{2265844:WVHEPQY3}"] (Austria had used the German translation, complete with the mistranslation).

9. Pretest the version resulting from adjudication.Rationale

One purpose of pretesting is to test the viability of the translation and to inform its refinement, as necessary, in preparation for final fielding. All instruments should be pretested before use. The best possible version achievable by the team development process should be targeted before pretesting (see Pretesting).

Procedural steps

See Pretesting.

Lessons learned

9.1 No matter how good the team translation, review, adjudication, and any assessment steps are, pretesting is likely to find weaknesses in design and/or translation [zotpressInText item="{2265844:WVHEPQY3},{2265844:TNMYF2MY}"].

10. Review, revise, and re-adjudicate the translation on the basis of pretesting. RationalePretesting results may show that changes to the translation are needed. Changes can be implemented as described below.

Procedural steps

10.1 Decide on the team required to develop revisions. This will differ depending on the nature and number of problems emerging from the pretest and on whether or not solutions are presented along with the problems.

10.2 If a one- or two-person team is chosen that does not include one of the translators, share any changes (tracked or highlighted) with a translator for final commentary, explaining the purpose of the revision.

10.3 Review the documentation from the pretest, considering comments for each question or element concerned.

10.4 Ensure that changes made in one section are also made, where necessary, in other places.

10.5 Copyedit the version revised after pretesting in terms of its own accuracy (consistency, spelling, grammar, etc.). Target language competence is required for this.

10.6 Copyedit the version revised after pretesting in its final form against the source questionnaire, checking for any omissions, incorrect filtering or instructions, reversed order items or response scale labels, etc. Competence in both target and source language is required for this.

10.7 Check in programmed applications that hidden instructions have also undergone this double copyediting (see Instrument Technical Design).

10.8 Present the copyedited and finalized version for final adjudication. The adjudication procedures for this are as before. Project specifics will determine in part who is involved in the final adjudication.

Lessons learned

10.1 It is extremely easy to overlook mistakes in translations and in copyediting. The review and adjudication steps offer repeated appraisals which help combat this, as do the documentation tools.

10.2 It is often harder to overlook certain kinds of mistakes if one is familiar with the text. It is better if the copyeditors are not the people who produced the texts.

10.3 Although copyediting is a learnable skill, good copyeditors must also have a talent for noticing small details. The senior reviewer should ensure people selected for copyediting work have this ability.

10.4 If the people available to copyedit have helped produce the translations, allow time to elapse between their producing the translation and carrying out copyediting. Even a few days may suffice.

10.5 Problems with incorrect instructions, numbering, filters, and omitted questions are quite common. They are often the result of poor copyediting, cut-and-paste errors, or inadvertent omissions, rather than 'wrong' translation. Thus, for example, reversed presentation of response scale categories is a matter of order rather than a matter of translation. It can be picked up in checking, even if the reversal may have occurred during translation.

10.6 Use a system of checking-off (ticking) material that has itself been tested for efficiency and usability. In iterative procedures such as review and revision, this checking-off of achieved milestones and versions and the assignment of unambiguous names to versions reduces the likelihood of confusing a preliminary review/adjudication with a final one (as an example, see the ESS Translation Quality Checklist [zotpressInText item="{2265844:CDZUNHWQ}"]. Automatic copyediting with Word will not discover typographical errors such as for/fro, form/from, and if/of/off. Manual checking is necessary.

11. Organize survey translation work within a quality assurance and control framework and document the entire process.Rationale

Defining the procedures used and the protocol followed in terms of how these can enhance the translation refinement process and the ultimate translation product is the most certain way to achieve the translation desired. Full documentation is necessary for internal and external quality assessment. At the same time, strong procedures and protocols do not resolve the question of what benchmarks should be applied for quality survey translation. [zotpressInText item="{2265844:RK729MUW}" format="%a% (%d%)"] discusses the need for research in this area.

Procedural steps

The steps involved in organizing a team translation are not repeated here. The focus instead is on what can be targeted in terms of translation quality.

11.1 Define survey translation quality in terms of fitness for use:

11.1.1 Fitness for use with the target population.

11.1.2 Fitness for use in terms of comparability with the source questionnaire.

11.1.3 Fitness for use in terms of producing comparable data (avoiding measurement error related to the translation).

11.1.4 Fitness in terms of production method and documentation.

11.2 Produce survey translations in a manner that adequately and efficiently documents the translation process and the products for any users of the documentation at any required stage in production (e.g. review, version production control, shared language harmonization, questionnaire design).

Lessons learned

11.1 The effort required to implement a well-structured and well-documented procedure and process will be repaid by the transparency and quality control options it makes possible. Thus, even simple Word or Excel templates make it easier to track the development of translations, to check that certain elements have not been missed, and to verify if and how certain problems have been resolved. These might begin with translator notes from the draft productions, and evolve into aligned translations in templates for review, later becoming templates for adjudication with translations proposed and comments on these. [zotpressInText item="{2265844:BCLSSQJ6}" format="%a% (%d%)"] provide examples of how Excel templates help guide quality control and assurance steps. An example of such a template used for documenting the whole translation history is the Translation and Verification Follow-up Form (TVFF) used by the ESS since Round 5 (see Appendix A for an example).

11.2 Once procedures become familiar and people gain practice in following protocols, the effort involved to produce documentation is reduced.

11.3 [zotpressInText item="{2265844:73HVKB69}" format="%a% (%d%)"] introduce the concepts of input and output documentation and demonstrate them using the European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging Risks (ESENER-2) in 2014 as a case study, taking into account the perspective of project management teams, translation teams, translation researchers, and end users of the survey data. While input documentation contains instructions on the translation product and process, concept clarifications, or other reference materials, output documentation includes the final translation with comments on problematic cases and adaptations, as well as the decisions on translation problems throughout all translation stages. The authors note the importance of software choice and functionality for both input and output documentation, as it is key to streamlining the work for all stakeholders during the translation process [zotpressInText item="{2265844:73HVKB69}" etal="yes"].

12. Translation procedures from the past (no longer recommended).After in-depth discussion of team translation procedures, other translation procedures often recommended in the past are briefly outlined here. The outlines concentrate on arguments against using such procedures anymore. The chapter briefly outlines other approaches sometimes followed to produce or check survey translations and indicates why these are not recommended here. For discussion, see [zotpressInText item="{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:4S267T9N}" format="%a% (%d%)"], [zotpressInText item="{2265844:WIZ9W4KX}" format="%a% (%d%)"], and [zotpressInText item="{2265844:KIP6EVCR}" format="%a% (%d%)"].

12.1 Machine translation: One of the main goals of machine translation is to greatly reduce human involvement in translation production, where word-based matches can be identified, and, it is assumed, cultural and dynamic aspects of meaning are reduced. However, survey questions are a complex text type with multiple functions and components whose complexities cannot be fully recognized by technology [zotpressInText item="{2265844:RK729MUW},{2265844:WVHEPQY3},{2265844:LAH6XJPS},{2265844:KIP6EVCR}" etal="yes"]. As a result, any reduction of human involvement in the decision-making process of survey translation through an automatic mechanism is ill-advised [zotpressInText item="{2265844:KIP6EVCR}" etal="yes"]. If a machine translation is used for questionnaire items, then careful review and adjudication of the resultant translation are necessary.

12.2 Do-it-yourself ad hoc translation: It is a mistake to think that just because someone can speak and write two languages, they will also be a good translator for these languages. Translation is a profession with training and qualifications. Translatology (under various names) is a discipline taught at the university level. Students of the translation sciences learn an array of skills and procedures and become versed in translation approaches and theories which they employ in their work. At the same time, as explained in the description of team translation following here, survey translation calls for not only a good understanding of translation, but also of the business of survey measurement and how to write good questions. Under normal circumstances, a trained translator should not be expected to have a strong understanding of survey practices and needs, hence the need for a team of people with different skills [zotpressInText item="{2265844:K4E3JQ52},{2265844:UJ7SVFJD},{2265844:2MJMKXPF},{2265844:RK729MUW},{2265844:LAH6XJPS},{2265844:KIP6EVCR}"].

12.3 Unwritten translation:

12.3.1 Sometimes bilingual interviewers translate for respondents as they conduct the interview acting as interpreters. In other words, there is a written source questionnaire that the interviewers look at but there is never a written translation, only what they produce orally on the spot. This is sometimes called 'on-sight' translation, 'on-the-fly' translation, or 'oral' translation.

12.3.2 Another context in which survey translation is oral is when interpreters are used to mediate between an interviewer speaking language A and a respondent speaking language B. The interviewer reads aloud the interview script in language A and the interpreter is expected to translate this into language B for the respondent and, most important, does not change the translation from one interview to the other. The interpreter is also expected to translate everything the respondent says in language B into language A for the interviewer. Research is quite sparse on the process of oral translation in surveys and how this affects interpretation, understanding, and data. Evidence available from recent investigations suggests that these modes of translation must be avoided whenever possible and that extensive training and briefing should take place if they must be used [zotpressInText item="{2265844:4S267T9N},{2265844:PNXGD7MM},{2265844:AP8Z23BE}"].

12.4 Translation and back translation: Even today, many projects rely on procedures variously called 'back translation' to check that their survey translations are adequate. In its simplest form, this means that the translation which has been produced for a target language population is re-(or back-) translated into the source language. The two source language versions are compared to try to find out if there are problems in the target language text. As argued elsewhere, instead of looking at two source language texts, it is much better in practical and theoretical terms to focus attention on first producing the best possible translation and then directly evaluating the translation produced in the target language, rather than indirectly through a back translation. Comparisons of an original source text and a back-translated source text provide only limited and potentially misleading insight into the quality of the target language text [zotpressInText item="{2265844:2MJMKXPF},{2265844:LAH6XJPS},{2265844:KIP6EVCR},{2265844:MF34AJEX},{2265844:RQS4BYQJ}"].

References [zotpressInTextBib style="apa" sortby="author"]